Suit fusing is a non-woven textile made of polymers used to strengthen jackets. It helps a jacket keep shape after being pressed, gives weight so it carries well on the body, and strengthens the cloth. Suit fusing is often used on the shoulders, at the cuffs, in the lapel, at the bottom of the suit, and at the vents at the back of the jacket.

Fusing is usually joined to the suit jacket using thermal bonding: The fusing and the cloth is pressed together at a heat of between 130 - 149C with pressure, and the fusing ‘sticks’ to the cloth via microscopic levels of adhesive.

There is much ill advice about suit fusing online due to misunderstanding about the adhesive and its composition. Here are the myths:

- Suit fusing damages the fabric - false

- Suit fusing causes “bubbles” - false

- Suit fusing is new and a result of 21st Century mass consumption - false

Suit fusing is very thin, often less than 1mm. It is soft, as light as air, and almost unnoticeable. It does not damage the fabric it is used with, and is in fact used to strengthen it.

Fusing helps a suit maintain its crisp shape and lines after pressing (pressing is when the suit goes through a process similar to ironing to give it curvature). It’s put at the end of the cuffs, in the lapels, and at the bottom of the suit jacket for just this purpose.

Fusing also helps strengthen cloth, especially light-weight materials, in areas that receive much wear. The shoulders, under the arm, elbows and at the neck often have small areas of fusing.

Fusing is a non-woven textile, made of various polymers including but not exclusively polyester. The first non-wovens were used in clothing in the 1940s and became popular in suit manufacturing, both by established tailors and large retailers, in the 1980s.

When fusing grew in popularity due to the benefits it gave a suit, consumers became aware of a problem described as "bubbling". Little bumps would appear after three or four years of wearing the jacket through the cloth. Bubbling was not caused by the fusing as many thought, but by poor quality adhesive that had low melting points.

Today, bubbling is no longer a problem as the adhesives used are much better, with a higher melting point of 130 - 149C, which is only a few degrees below which the cloth itself burns. Whereas before trips to the dry cleaners would cause bubbling, this is no longer a problem and anyone saying so is thirty years behind. Furthermore, fusing is now joined to the fabric using a microdot thermal bonding technique (in most cases). The amount of adhesive used is minuscule. You can see the microdots in the photo below:

Before fusing, suit jackets tended to be fully canvassed. A horse hair and wool woven canvas would fill the inside of the jacket, providing the same benefits: strengthening the cloth, giving it weight so it hangs well, helping the jacket maintain its shape. This was fantastic for when working outdoors, or in cold offices.

Today with central heating and temperature controlled offices, fully canvassed jackets are more of a problem than a benefit. They are heavy, thick and warm. To have canvassing from top to bottom negates any benefit of light-weight cloths: if you want to feel a light cloth, then there's no point filling it with something heavy and thick. Full canvassing is too warm for everyday use and now used mostly for outdoor hunting and sports jackets.

It is still possible to ask for a fully canvassed jacket, and horse hair blends are still used. Increasingly though it is a wool and cotton blend.

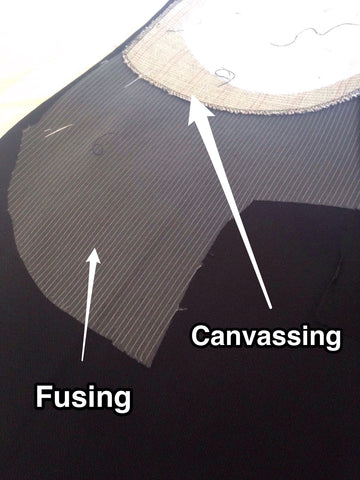

To achieve the best of both fusing and canvassing, tailors now produce what's called a half-canvassed jacket. Fusing is used as described above, and canvassing hangs over the shoulders and chest to provide the strength, shape and warmth. In the picture below you can see both canvassing and fusing.

In almost all cases the default option for suit tailors now is to produce a half-canvassed jacket and this is what you should ask for. Perhaps for a tweed jacket to be worn outside while shooting, deer stalking or hunting might a fully canvassed jacket be good.